The recent hyperbolic arrival of the Apple Watch inspires this blog post.

We confess to certain prejudice on the subject; after all, we love, collect and sell vintage watches, and can’t help but smile wryly to ourselves as the idea of the Apple Watch being thought of as a revolutionary advance. After all, it does have to pair with an expensive Smartphone and needs a battery to be something other than a paperweight. Under those circumstances, is a watch that doesn’t work still a watch?

Philosophical musing aside, our oldest offering – a Gallet Electa trench watch from 1910 – is contentedly ticking away after nearly 100 years.

We find it hard to believe that any Apple Watch will be running in 2115 – after all, who will supply the batteries, who the new circuit boards?

Ah, the joys of a mechanical watch: one of the winding wheels had been broken when we acquired the Gallet, but it was a relatively simple matter for our old school watchmaker to magic us up a replacement wheel.

Tick, tock, tick, tock. We know our watches won’t tell us where we are and with whom we’re to meet when. But they are what they are, travellers from simpler times.

And so it is that we find our minds turning to earlier – no doubt more discreet – revolutions in horology. Wearing a watch on your wrist seems so obvious to us now, but early watches were mostly carried, warm and safe, in a gentleman’s pocket. But the arrival of World War 1 took watches out of gentlemen’s pockets and into leather cases called wristlets, which were then strapped onto a man’s wrist.

A small detail, maybe, but evidence of a social revolution: gentlemen were now actively engaging in physical activities and needed their hands free to work. It didn’t take long before wristlets evolved into the watches we would recognise today as wristwatches.

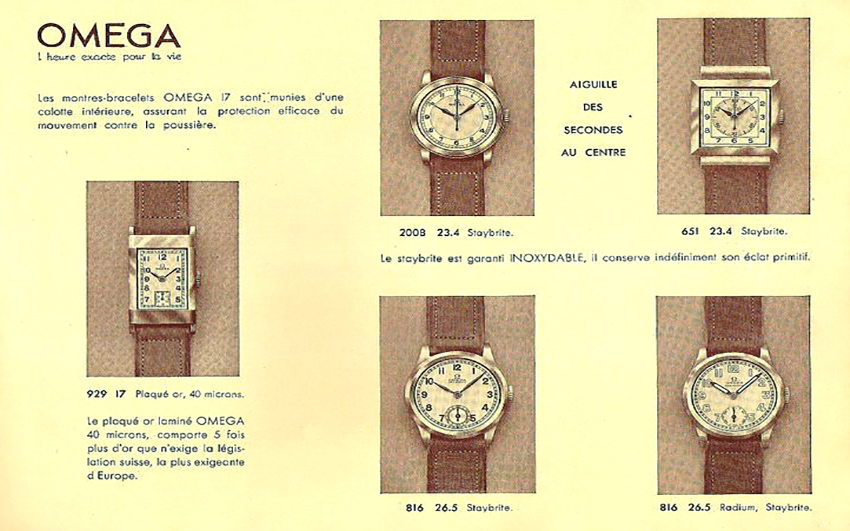

Inside watches, the revolution continued, too. Miniaturisation took hold, shrinking the movement. But the second hand was still firmly rooted at the bottom of the dial until Omega and others introduced the sweep second hand on the same centre as the hour and minute hand.

Omega’s revolutionary idea was to create a series of watches with longer than usual second hands and a clear, easy-to-read outer chapter ring, which they targeted at the medical community and called the Medicus. The idea was to enable doctors to more easily read their patient’s pulses and still have one hand free.

Omega list several models to which they attribute the name Medicus; for complete accuracy, though, it has to be said that there are independent historians who dispute this and maintain that there was only ever one, the CK 651.

Our CK 651 has been lovingly restored, both mechanically and aesthetically. At some point, someone had seen fit to entirely remove the dial finish right down to bare metal. Like most serious collectors, we’re loath to refinish dials; it’s generally hard to get it right for one thing, so we try to avoid doing so. But we felt this was justified and so set out to research our own example. We wrote, emailed and called every dial refinishing company in the Western world asking if they could re-do it as close to original as possible. We finally found only one such craftsman–no one else could do it as exactly–and feel pleased by the result.

We’ve also taken the trouble to accredit our watch by way of obtaining an official extract from the Omega archive, which confirms that ours was made in February 1938 and sold to the United Kingdom.

Omega catalogue ca. 1937 showing CK 651 (one of several dial variations offered)

© 2015 Time. All rights reserved